Every day, security teams at enterprises around the world open their dashboards to find hundreds of new common vulnerabilities and exposures (CVE) alerts from their software composition analysis (SCA) tools. They dutifully begin the process of validation: Is this a real threat? Does it affect our actual usage? Can we safely ignore it? Hours later, they’ve worked through a fraction of the queue, and tomorrow will bring hundreds more.

This is alert fatigue, and it’s costing organizations far more than most realize. Security teams waste 10,000 hours and $500,000 annually validating unreliable and incorrect vulnerability alerts. More than 60% of security professionals estimate their security function spends over three hours per day chasing false positives, with nearly 30% estimating over six hours.

Traditional SCA tools like Snyk, Black Duck, and others are doing their job by detecting issues and generating alerts, but those alerts don’t address the fundamental architectural issue that creates so many vulnerabilities in Python environments in the first place.

Where Python Vulnerabilities Actually Live

The overwhelming majority of vulnerabilities in Python-driven data science and machine learning environments don’t actually originate in Python code at all. They live in the compiled binary libraries that Python packages depend on.

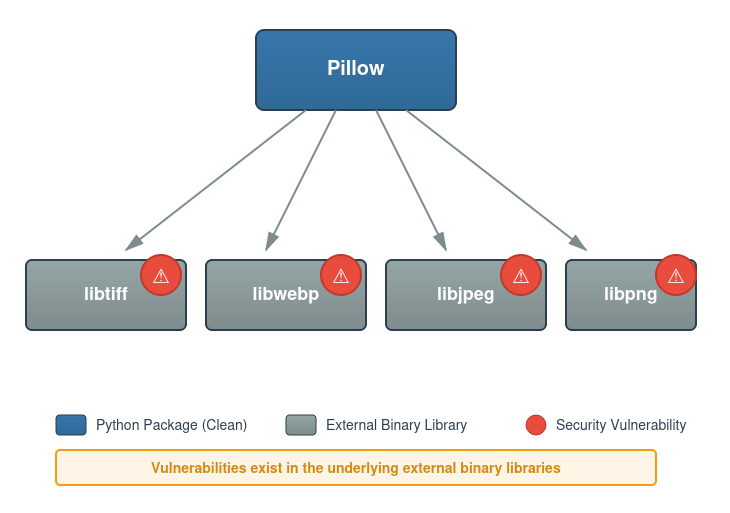

Consider Pillow, the popular Python image processing library. SCA tools frequently flag Pillow as having critical vulnerabilities, but the Python code in Pillow isn’t to blame. The vulnerabilities exist in the underlying external binary libraries (libtiff, libwebp, libjpeg, and others) that Pillow uses to manipulate image data.

This pattern repeats across the Python ecosystem. When NumPy has a security issue, it could be associated with the BLAS or LAPACK libraries (specialized mathematical libraries that perform the actual number-crunching). When cryptography packages trigger alerts, OpenSSL or another cryptographic external binary library may actually be at fault.

Why does this matter? Because the way these dependencies are managed has profound implications for security and remediation.

The Bundled Binary Challenge

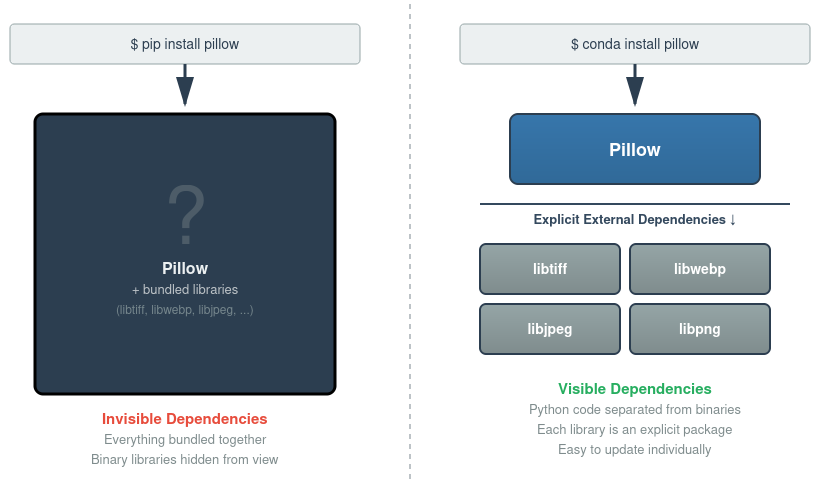

If you install Pillow using pip, it doesn’t just install Python code. It installs “wheels,” which are pre-packaged bundles that contain the Python code along with copies of all the necessary binary libraries.

From the user’s perspective, they asked for Pillow and they got Pillow. What they don’t realize is they also got libtiff version X, libwebp version Y, libjpeg version Z, and potentially many other binary components.

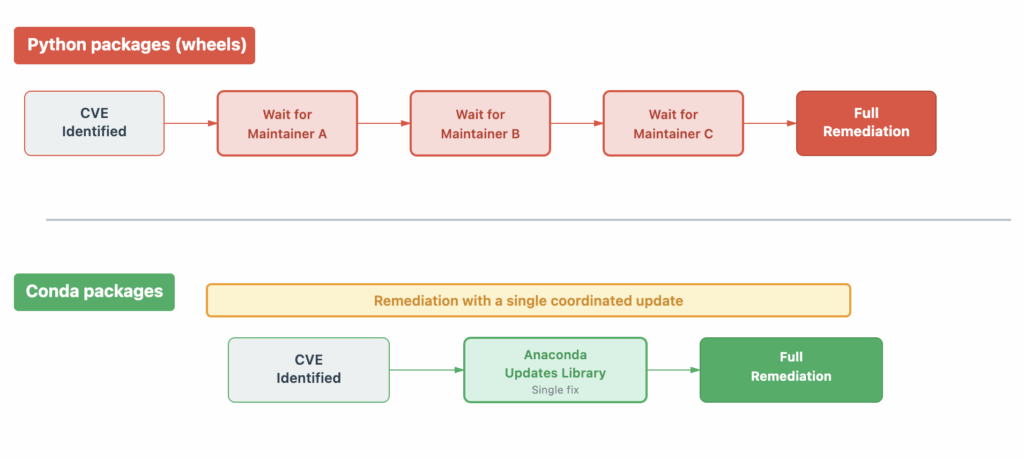

This bundling approach creates an invisible problem. Your environment might contain 10 different packages, each bundling their own copy of an external binary library at different versions. You have no easy way of knowing this. And when a vulnerability is discovered in one of these bundled libraries, security scanners attribute it to the Python package that contains it. The alert says “Pillow is vulnerable,” when the reality is “the libwebp library bundled inside Pillow is vulnerable.” The vulnerability in libwebp may impact multiple packages (e.g., imageio, scikit-image). Remediation then requires waiting for each package maintainer to rebuild their wheel with an updated version. Each package has its own release cycle, maintainer availability, and testing requirements, so a single vulnerability in libwebp could mean waiting weeks or months for fixes.

A Different Architecture

Anaconda’s approach to Python package management follows a fundamentally different architecture. When you install Pillow using conda, the Pillow package contains the Python code. The external binary libraries it depends on are pulled in as separate, explicit conda packages. When you run conda install pillow, you see exactly what you’re getting: Pillow itself, plus libtiff version X, libwebp version Y, libjpeg version Z, and so on.

This architectural difference means you can see every external binary library in your environment as a first-class package. It also means that when libwebp has a vulnerability, it’s correctly identified as a libwebp issue (not misattributed to every package that uses it). Further, when that vulnerability is discovered, Anaconda can rapidly respond by updating that single library across all packages that depend on it.

For example, CVE-2023-5129 was a critical heap buffer overflow vulnerability in libwebp that affected multiple Python packages. When CVE-2023-5129 was discovered in libwebp, Anaconda updated libwebp once, and all the packages depending on it (Pillow, scikit-image, and others) were immediately protected.

The Anaconda packaging team monitors CVEs impacting external binary libraries so when these CVEs are detected they can quickly rebuild affected packages and coordinate updates across the ecosystem. No waiting for individual maintainers, no staggered updates over weeks.

Building Security In Instead of Just Scanning It Out

Traditional SCA tools operate on a detection model. They scan your installed packages and alert you to CVEs. This is valuable and necessary, but it’s fundamentally reactive.

Anaconda incorporates security at the start by building from vetted source code using secure, consistent, reproducible processes rather than simply mirroring what’s available on PyPI. Anaconda packages rely on minimal system libraries, create reproducible environments across different operating systems, and enable deployment on minimal container images for reduced attack surface.

The Value of Layered Security

Anaconda’s approach doesn’t replace traditional SCA tools. Instead, it changes the security paradigm upstream from where those tools operate.

Traditional SCA tools provide detection, monitoring, and alerting across your entire software portfolio. Anaconda addresses vulnerabilities by managing dependencies explicitly, building packages with security-first design, and providing rapid, targeted remediation capabilities.

Consider how these tools complement each other in practice. Your SCA tool might detect a vulnerability in a package you’re using, and that’s valuable information. But what’s your remediation path? If you’re using pip and that vulnerability is in a bundled binary library, you’re waiting on Python package maintainers to rebuild their wheels. If you’re using Anaconda and that same binary library is managed as an explicit dependency, Anaconda can update it directly, often within hours. The SCA tool provides the detection, and Anaconda provides the fix.

Making a Shift From Better Scanning to Better Building

Alert fatigue isn’t inevitable. It’s a symptom of an architectural approach that bundles dependencies invisibly and detects vulnerabilities reactively. When you manage dependencies explicitly and build them professionally from the start, there are fewer problems to alert on. The alerts you do receive are accurate and remediable.

For organizations evaluating their security stack, the question isn’t “why do I need this when I have Snyk?” It’s “how do I close the architectural security gap that scanning alone can’t fix?”

The answer is complementary security. Build a secure foundation with explicit dependency management, and use traditional SCA tools for comprehensive monitoring and detection. Together, these approaches provide the layered protection that neither can achieve alone.

Learn more about package security with Anaconda Core.