Introduction

As I write and present about Python and its future, I regularly draw a distinction between Python the language and the Python interpreter. I believe that distinction is really important, but I’ve generally glossed over it because it’s never been the main topic. I’ve now officially gotten enough questions asking “What is the Python interpreter?” that I’m making it the main topic. If you’ve asked that question yourself, this article is for you.

I’ll cover what interpreters and interpreted languages are (with a focus on Python), how they compare to compiled languages, and why you should care. And, if you make it all the way to the end, I’ll talk about some of the things that are special about Python and how it blurs those lines.

The TL;DR

Computers don’t directly understand the programming languages we use (or spoken languages for that matter), so they need a translator. Some programs are translated when they’re created and shipped in this computer-readable form. Others are translated when you run them.

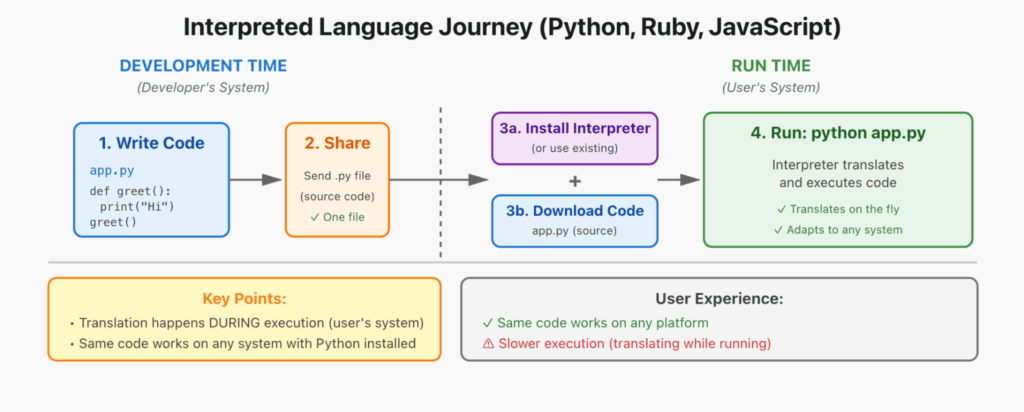

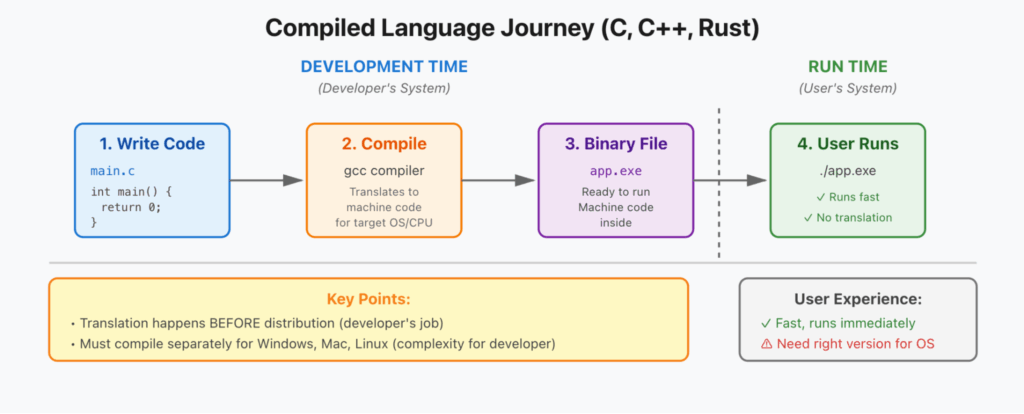

Python is an interpreted language. This means it uses an interpreter to convert your code to machine code (instructions the computer understands) while the program is running. This is different from compiled languages like C++ or Rust, which use a compiler to translate your code to machine code at development time (before you distribute the program).

What this means is:

- Interpreted code is generally more flexible and dynamic because the code is being evaluated as it’s used

- Compiled code is generally faster because there is more time to optimize at development time since you’re translating it to machine code in advance

- Interpreted code is easier to distribute because developers ship one piece of code and it will run on any machine with a compatible interpreter

- Compiled code is easier for users to run because you’re downloading a single file/application for your machine that requires minimal additional set up

Python has been so successful because it leverages the strengths of being an interpreted language, while the community and companies like Anaconda have worked to smooth over many of the disadvantages above.

The term “Python” commonly refers to both the language itself and the interpreter. When we say “the interpreter,” we’re specifically talking about the program that translates Python code into something your computer understands (usually CPython, a reference interpreter written in C, which we’ll talk about later).

Why Should You Care?

First of all, you have a choice. When creating applications, you can select the language type that matches your needs. You’ll also see that you have tools at your disposal to do a little bit of both. The point is, whatever language you choose has implications for your application that you should know about.

An interpreted language makes sense for:

- Rapid prototyping: Need to test ideas quickly

- Cross-platform tools: Want code that runs everywhere

- Data science/scripting: Flexibility and ease of coding matters more than raw speed

- Learning programming: Easier debugging and experimentation

A compiled language makes sense for:

- Performance-critical apps: Games, operating systems, embedded systems

- Resource-constrained devices: Every millisecond and megabyte counts

- Closed-source distribution: Don’t want to ship source code

Quick Comparison

| Aspect | Interpreted (Python) | Compiled (C/C++) |

|---|---|---|

| Translation timing | During program execution | Before distribution |

| Execution speed | Slower | Faster |

| Developer flexibility | High – dynamic features | Lower – static |

| Code portability | Write once, run anywhere | Compile for each platform |

| Distribution | Source code + dependencies | Single executable file |

| Use case | Rapid development, scripting, data science | Performance-critical apps, games |

Why Do We Need Compilers and Interpreters, Anyway?

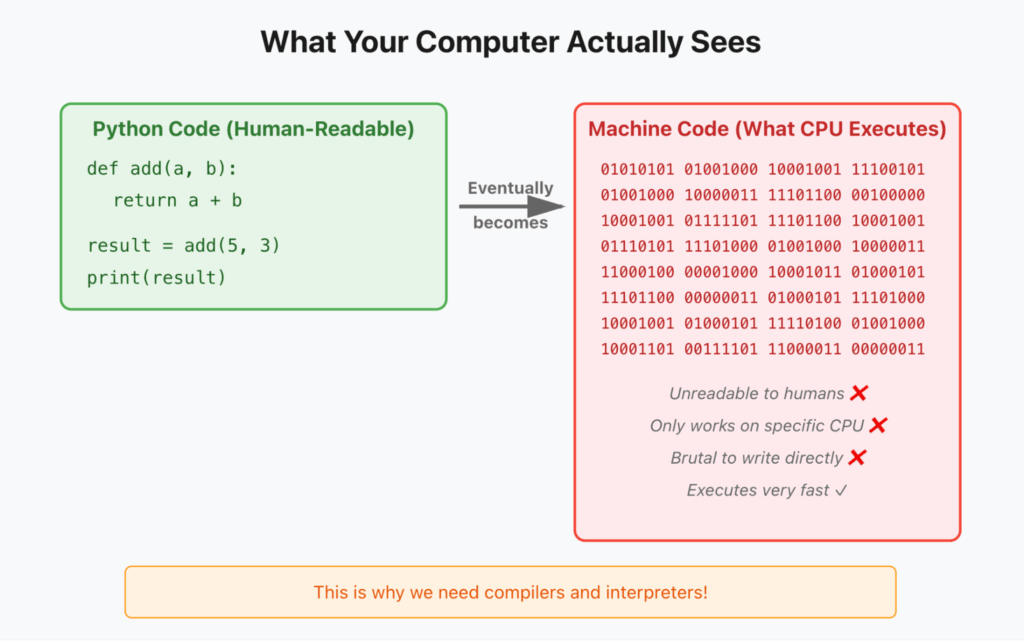

So, interpreters and compilers both convert programming languages into machine code. But why is that translation necessary in the first place? Why not just write machine code directly?

The reason is because machine code is a pain to read, brutal to write, and only works on the system it was written for. In order for software to take off, there needed to be an easier way to write and distribute code.

High-level languages like Python, C++, etc. exist to solve that problem. They let you write code that’s human-readable and (mostly) portable. But that means something needs to translate them into low-level instructions your system understands: load this information, save this information, add this to that, etc.

Compilers and interpreters are just two different approaches for handling that translation. To understand how they differ in practice, here’s an analogy…

When Acting Like an Interpreter: Going to the Store

I get a text that says, “Drive to the store to pick up milk.” From there, I would execute a number of thoughts and actions, like this:

- First, I need to grab the keys for the car

- The last place I left them was on the table by the door

- I grab the keys off the table

- I walk out to my car in the garage and get in

- My brain figures out, “I’m home now, and the closest store is HEB a mile away”

- I press the start button and leave the garage

- etc.

I won’t bore you with every step, but there are some things I want to highlight. I received a simple instruction, and at each step I took actions based on what I knew about the environment. I knew where my keys were, but if I didn’t, I could figure it out. I knew the closest store, but if that store was closed, I could have gone to another. I knew how to operate my car, but if I sat in a different one, I’d quickly adjust to its controls.

There was more thinking involved on my part, more cognitive load, and I needed to make decisions as I went. But I also had the flexibility to complete the task any way I saw fit.

When Acting Like a Compiler: Going to the Store

Instead of a simple text, I receive a lengthy set of instructions that says, “Follow these instructions exactly.”

- Walk to the table by the door

- Pick up the keys off the table

- Go into the garage

- Get in the car

- Press the button in the middle of the center console

- Back up for 30 feet out of the garage

- Go east 500 feet

- etc.

This scenario is very different. I don’t need to think much at all. I just need to follow the steps in sequence. I can do this much faster (speed limits aside), especially because whoever created the instructions optimized them exactly for my situation: where I was, where I was going, what my car looked like, and so on.

But if I left my keys somewhere else, or I wasn’t at home, or I had a different car, the instructions wouldn’t work. There would have to be massive work upfront to create different instructions for different scenarios, but then the tasks could be performed by anyone. They don’t need any information about the situation. They just follow the steps.

Neither of those scenarios is “better” than the other. They’re just different. There are advantages and disadvantages to each, but there are tradeoffs on preparation, flexibility, and speed. These are the decisions we make when we choose a programming language.

The Reference Python Interpreter: CPython

If you’ve made it this far, congratulations! It’s going to get a little more technical here, so don’t say I didn’t warn you.

Whenever we talk about a Python interpreter, we’re usually talking about CPython, the reference interpreter supported and developed by the Python community. As the reference interpreter, CPython is by far the most common, but there are other implementations out there: Jython (Python interpreter written in Java), IronPython (.NET), MicroPython (for microcontrollers), PyPy, and even tuned versions of CPython for specific use cases, like Cinder. The point here is that you can use any interpreter you want as long as it matches the output of the reference implementation and the Python spec.

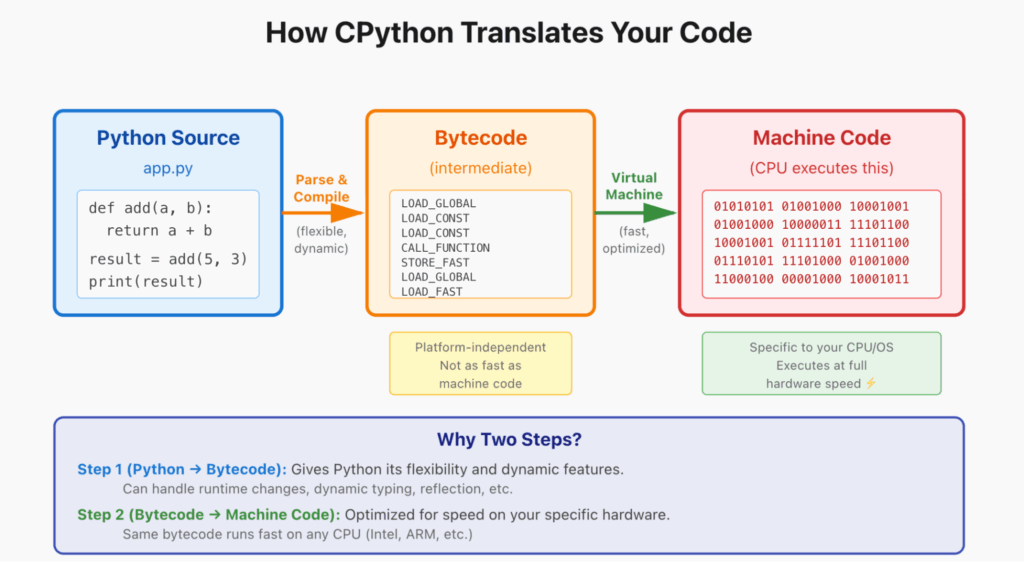

The Python interpreter actually converts your code first to something called “bytecode,” then that bytecode is translated to fast machine code by something called a virtual machine. The bytecode-to-machine-code translation is fast and optimized for whatever hardware the interpreter runs on, while the Python-to-bytecode translation is where you get all the flexibility and dynamic features of the language.

Most of the time, when someone runs python someapp.py, that’s CPython running. You may find it curious that CPython is written in C, but when you think about it, CPython has a very specific job. You want it to be as optimized and performant as possible, and you’re OK with the penalty of having to build it specifically for every platform so it can take full advantage of that platform’s capabilities.

Where Python Blurs the Lines

Though everything above still holds, there are some really interesting things about Python that have enabled it to overcome many of the general challenges of interpreted languages. These are some of the reasons Python has grown from a scripting language, to a web application language, to a high-performance data science language, to the de facto language for AI.

Python is Just the Glue

The most important factor in Python’s evolution is its flexibility in running binaries and compiled programs from other languages. This isn’t even really the exception—it’s kind of the rule. Yes, when you write a Python application, you’re probably writing all Python code yourself. But if you look at the most common libraries for Python, you’ll find mostly C, C++, Fortran, and a number of other languages. This is the key to Python’s success in performance-critical and data-intensive fields, and it’s the reason why “Python is slow” is not the full story.

Python is extremely easy to use, write, and understand. But under the hood, you have an ecosystem of high-performance packages written in compiled language to provide maximum performance. Python is the developer interface, or “glue,” for a vast selection of libraries, frameworks, and tools to handle the most common tasks efficiently. You get the best of both worlds: You can quickly write something in Python, but if you need to optimize part of it, you can use whatever language you want or find someone else’s library that’s already optimized.

Compiled Python?

Another development in the Python community is the growth of efforts to compile Python. You have languages like Cython, which is a superset of Python that can actually compile Python into binaries and is commonly used to optimize Python libraries. You also have JIT (Just-in-Time) compilers like Numba that compile designated code sections into fast machine code when you first run the application.

However, all of these tools come with tradeoffs. They either don’t work with all existing Python code, require you to change or rewrite your Python code, or only accelerate certain types of code. There are exciting new initiatives, like the SPy language, which aim to get you close to the best of both worlds by essentially splitting your code into compilable and dynamic sections that need an interpreter. That means you can use all of the goodness of Python while optimizing as much of it as you can.

Summary

Programming is a broad and diverse discipline, and the massive range of languages is not just based on taste. There are important technical decisions behind them all. Those technical decisions are what make Python special.

- Python is interpreted: Code is translated to machine code while running, not before distribution

- CPython is the standard: The reference Python interpreter, written in C, used by most Python programs

- Two-stage translation: Python → bytecode → machine code gives flexibility and reasonable performance

- The real secret: Python serves as the glue connecting easy-to-write code with high-performance compiled libraries

- This is why Python dominates AI/ML: You get productivity AND performance where it matters

The next time someone says “Python is slow,” you’ll understand the nuance: pure Python code executing in the interpreter can be slower than compiled code, but real-world Python applications leverage compiled libraries for performance-critical work, giving you the best of both worlds.